Action on wet markets amid COVID-19, Protected shark fins traced to place-of-catch, Arctic will have an iceless summer by 2050, Breakthrough to help save reefs from dying and much more…

The World Health Organization (WHO) is calling for stricter safety and hygiene standards when wet markets reopen. The WHO also says governments must rigorously enforce bans on the sale and trade of wildlife for food. The start of the pandemic was linked to a market in Wuhan, where wildlife was on sale. Wet markets are common in Asia, Africa, and elsewhere, selling fresh fruit and vegetables, poultry, fresh meat, live animals, and sometimes wildlife. The WHO is working with UN bodies to develop guidance on the safe operation of wet markets, which it says are an important source of affordable food and a livelihood for millions of people all over the world.

The World Health Organization (WHO) is calling for stricter safety and hygiene standards when wet markets reopen. The WHO also says governments must rigorously enforce bans on the sale and trade of wildlife for food. The start of the pandemic was linked to a market in Wuhan, where wildlife was on sale. Wet markets are common in Asia, Africa, and elsewhere, selling fresh fruit and vegetables, poultry, fresh meat, live animals, and sometimes wildlife. The WHO is working with UN bodies to develop guidance on the safe operation of wet markets, which it says are an important source of affordable food and a livelihood for millions of people all over the world.

The Australian government is calling for the G20 countries to take action on wildlife wet markets, calling them a “biosecurity and human health risk”. Australia is not yet calling for a ban – but says its own advisers believe they may need to be “phased out”. “Wet markets” are marketplaces that sell fresh food such as meat and fish. But some also sell wildlife – and it’s thought the coronavirus may have emerged at a wet market in Wuhan that sold live “exotic” animals. The Huanan market in Wuhan reportedly offered a range of animals including foxes, wolf cubs, civets, turtles, and snakes.

The Australian government is calling for the G20 countries to take action on wildlife wet markets, calling them a “biosecurity and human health risk”. Australia is not yet calling for a ban – but says its own advisers believe they may need to be “phased out”. “Wet markets” are marketplaces that sell fresh food such as meat and fish. But some also sell wildlife – and it’s thought the coronavirus may have emerged at a wet market in Wuhan that sold live “exotic” animals. The Huanan market in Wuhan reportedly offered a range of animals including foxes, wolf cubs, civets, turtles, and snakes.

3. Hammerhead shark fins in Hong Kong market traced to Eastern Pacific

For the first time, researchers have traced the origins of shark fins from the retail market in Hong Kong back to the location where the sharks were first caught. This will allow them to identify “high-risk” supply chains for illegal trade and better enforce international trade regulations. Florida International University’s Marine Scientist Demian Chapman led a team based in the United States and Hong Kong — the Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China — to conduct DNA analysis on shark fins from scalloped hammerhead sharks (Sphyrna lewini). One of the most common and valuable species in the trade, these sharks face an increasing risk of overexploitation — and possibly extinction.

4. The Arctic will have an iceless summer by 2050

The Arctic Ocean will see an iceless summer within the next 30 years, according to a new study looking at the impact of climate change on the region. The study, conducted by McGill University in Montreal, found that the impact of climate change could have “devastating consequences for the Arctic ecosystem” by the year 2050, according to USA Today. Satellite recordings started tracking Arctic ice in the summer of 1979 and have reported a loss of 40 percent of its area and 70 percent its volume in recent years.

The Arctic Ocean will see an iceless summer within the next 30 years, according to a new study looking at the impact of climate change on the region. The study, conducted by McGill University in Montreal, found that the impact of climate change could have “devastating consequences for the Arctic ecosystem” by the year 2050, according to USA Today. Satellite recordings started tracking Arctic ice in the summer of 1979 and have reported a loss of 40 percent of its area and 70 percent its volume in recent years.

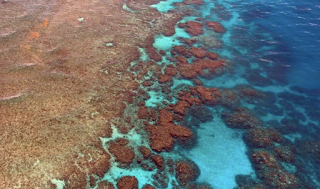

The Florida Aquarium has made a breakthrough that will help save “America’s Great Barrier Reef,” the third-largest coral reef in the world. For the first time in world history, the aquarium in Florida has successfully reproduced ridged cactus coral in human care. The corals are just one of a variety of species rescued from Florida’s waters by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and NOAA Fisheries after coral reefs in the state began undergoing a major disease outbreak that started in 2014.

The Florida Aquarium has made a breakthrough that will help save “America’s Great Barrier Reef,” the third-largest coral reef in the world. For the first time in world history, the aquarium in Florida has successfully reproduced ridged cactus coral in human care. The corals are just one of a variety of species rescued from Florida’s waters by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and NOAA Fisheries after coral reefs in the state began undergoing a major disease outbreak that started in 2014.

6. Extinction of threatened megafauna would lead to huge loss in functional diversity

In a paper published in Science Advances, an international team of researchers have examined traits of marine megafauna species to better understand the potential ecological consequences of their extinction under different future scenarios. Defined as the largest animals in the oceans, with a body mass that exceeds 45kg, examples include sharks, whales, seals, and sea turtles. These species serve key roles in ecosystems, including the consumption of large amounts of biomass, transporting nutrients across habitats, connecting ocean ecosystems, and physically modifying habitats.

To address plastic pollution plaguing the world’s seas and waterways, Cornell University chemists have developed a new polymer that can degrade by ultraviolet radiation, according to research published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society. “We have created a new plastic that has the mechanical properties required by commercial fishing gear. If it eventually gets lost in the aquatic environment, this material can degrade on a realistic time scale,” said lead researcher Bryce Lipinski, a doctoral candidate in the laboratory of Geoff Coates, professor at Cornell University.

To address plastic pollution plaguing the world’s seas and waterways, Cornell University chemists have developed a new polymer that can degrade by ultraviolet radiation, according to research published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society. “We have created a new plastic that has the mechanical properties required by commercial fishing gear. If it eventually gets lost in the aquatic environment, this material can degrade on a realistic time scale,” said lead researcher Bryce Lipinski, a doctoral candidate in the laboratory of Geoff Coates, professor at Cornell University.

8. Surface feeding could provide more than just snacks for New Zealand blue whales

Feeding at the ocean’s surface appears to play an important role in New Zealand’s blue whales’ foraging strategy, allowing them to optimize their energy use, Oregon State University researchers suggest in a new study. Blue whales are the largest mammals on Earth. Because of their enormous size, the whales must carefully balance the energy gained through their food intake with the energetic costs of feeding, such as diving, holding their breath or opening their mouths, which slows their movement in the water. Adding to the challenge: their prey are tiny krill and they must find and eat large volumes of them to make any energetic headway.

Philadelphia’s ban on single-use plastic bags will be delayed until January due to the coronavirus pandemic, Mayor Jim Kenney announced Wednesday. The ban, which Kenney signed into law in December and had been scheduled to take effect July 2, “is no longer realistic,” he said at a news conference. The announcement came as welcome news to retailers but was met with confusion and disappointment from environmental groups and Councilmember Mark Squilla, who sponsored the legislation.

Philadelphia’s ban on single-use plastic bags will be delayed until January due to the coronavirus pandemic, Mayor Jim Kenney announced Wednesday. The ban, which Kenney signed into law in December and had been scheduled to take effect July 2, “is no longer realistic,” he said at a news conference. The announcement came as welcome news to retailers but was met with confusion and disappointment from environmental groups and Councilmember Mark Squilla, who sponsored the legislation.

Current marine protected areas in the Southern Ocean need to be at least doubled to adequately safeguard the biodiversity of the Antarctic, according to a new CU Boulder study published today, Earth Day, in the journal PLOS ONE. Proposals under consideration by an international council this year would significantly improve the variety of habitats protected, sustain fish populations and enhance the region’s resilience to the effects of climate change, the authors say.

Current marine protected areas in the Southern Ocean need to be at least doubled to adequately safeguard the biodiversity of the Antarctic, according to a new CU Boulder study published today, Earth Day, in the journal PLOS ONE. Proposals under consideration by an international council this year would significantly improve the variety of habitats protected, sustain fish populations and enhance the region’s resilience to the effects of climate change, the authors say.

11. Caribbean coral reef decline began in the 1950s and ’60s from human activities

12. Tire industry pushes back against evidence of plastic pollution

A growing body of scientific research linking tire wear to microplastic pollution, as well as increased scrutiny from lawmakers in the European Union (EU), has led the $180 billion-a-year tire industry to fight back. The companies have stepped up lobbying with EU lawmakers weighing tougher regulations on tire wear, according to lawmakers and LobbyFacts.eu, a website that tracks EU lobbying data. They are also quickly countering scientific studies on tires and microplastic pollution with ones of their own that say tire particles present no significant risk to humans and the environment.

13. Endangered Mediterranean monk seals get help from a unique intervention

Conservationists are celebrating exciting new footage that reveals an endangered Mediterranean monk seal making use of an artificial breeding ledge they have created to aid in the species’ recovery. The footage, which shows a young adult female, is the first time that this species has been recorded using an artificial ledge, raising hopes that this unique habitat restoration effort will boost efforts to save monk seals from extinction.

A new method of detecting patches of floating macroplastics—larger than 5 millimeters—in marine environments is presented in Scientific Reports this week. The approach, which uses data from the European Space Agency Sentinel-2 satellites, is able to distinguish plastics from other materials with 86% accuracy. Lauren Biermann and colleagues identified patches of floating debris from Sentinel-2 data based on their spectral signatures—the wavelengths of visible and infrared light they absorbed and reflected.

A new international study led by Monash University climate scientists has found reef sand is dissolving much quicker than previously thought due to the impact of microbes. The study, published recently in Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, was led by Dr. Adam Kessler from the School of Earth, Atmosphere, and Environment. “We know that climate change is acidifying the oceans,” Dr. Kessler said. “And we know that this is bad for ocean life, such as coral, shellfish, and plankton.

A new international study led by Monash University climate scientists has found reef sand is dissolving much quicker than previously thought due to the impact of microbes. The study, published recently in Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, was led by Dr. Adam Kessler from the School of Earth, Atmosphere, and Environment. “We know that climate change is acidifying the oceans,” Dr. Kessler said. “And we know that this is bad for ocean life, such as coral, shellfish, and plankton.

———————————————–